Rhizomatic Sounds Across Time, Space, & Memory:

The Robert, the Russell, and the Holy Eno

I grew up in a small village outside of Darmstadt, Germany – an hour south of Frankfurt.

My father played a lot of jazz growing up; Thelonious Monk, Abdullah Ibrahim, especially Charles Mingus. Even my initials are a nod to Charles Mingus: C(ara) M(anuela), but also C(ara) M(ayer). I resented this kind of music when I was young. It sounded like pure chaos – sounds that didn’t belong to a single category; not even instruments, just noise with no structure.

Over the years, I began to grow passionate about music; but I saw nothing of myself in my surroundings. Frankfurt was filled with bankers, and all of its cultural centers seemed to be no more than vessels and vestiges of their wealth; a place to take your business partner out for lunch, show him the new Monet. No one my age was interested in music or art from Germany – didn’t even know about it – and neither did I. I resented Germany, was exasperated by it’s cold, impersonal glass architecture, shadow-puppet-like cultural institutions; assumed its art to be bland and by-gone.

Last year, I began to discover that the sound I had loved in my youth – the heavily distorted strumming of guitars, either so close to ambient that it could put you to sleep, or so close electronic music that it was almost appropriate to play at a party – had been a copy of a German sound: Krautrock.

It wasn’t until I was in a café in Seoul reading an exhibition catalogue on Nam June Paik and John Cage, that I realized that these two had met in Darmstadt, a city in which I had spent thousands of hours walking around, bored. Not only that, but Karlheinz Stockhausen and Morton Feldman had lectured there. There was even a group of musicians called The Darmstadt School. Clearly the history I had associated with German music was neither divorced from the music I already loved, nor as linear as I had expected it to be, and in fact, emerged from, and keeps expanding from its own circles, beyond itself – ingesting and digesting a wide range of genres, musical- and philosophical ideas – spitting them back out a-new in unexpected places.

The following pages record the discoveries I made about music in connection to my home and memory, a visual demonstration of how rhizomatic these discoveries were and continue to be both to me and to each other; and especially how these discoveries have shaped my awareness of the ability of music to make the force of time audible.

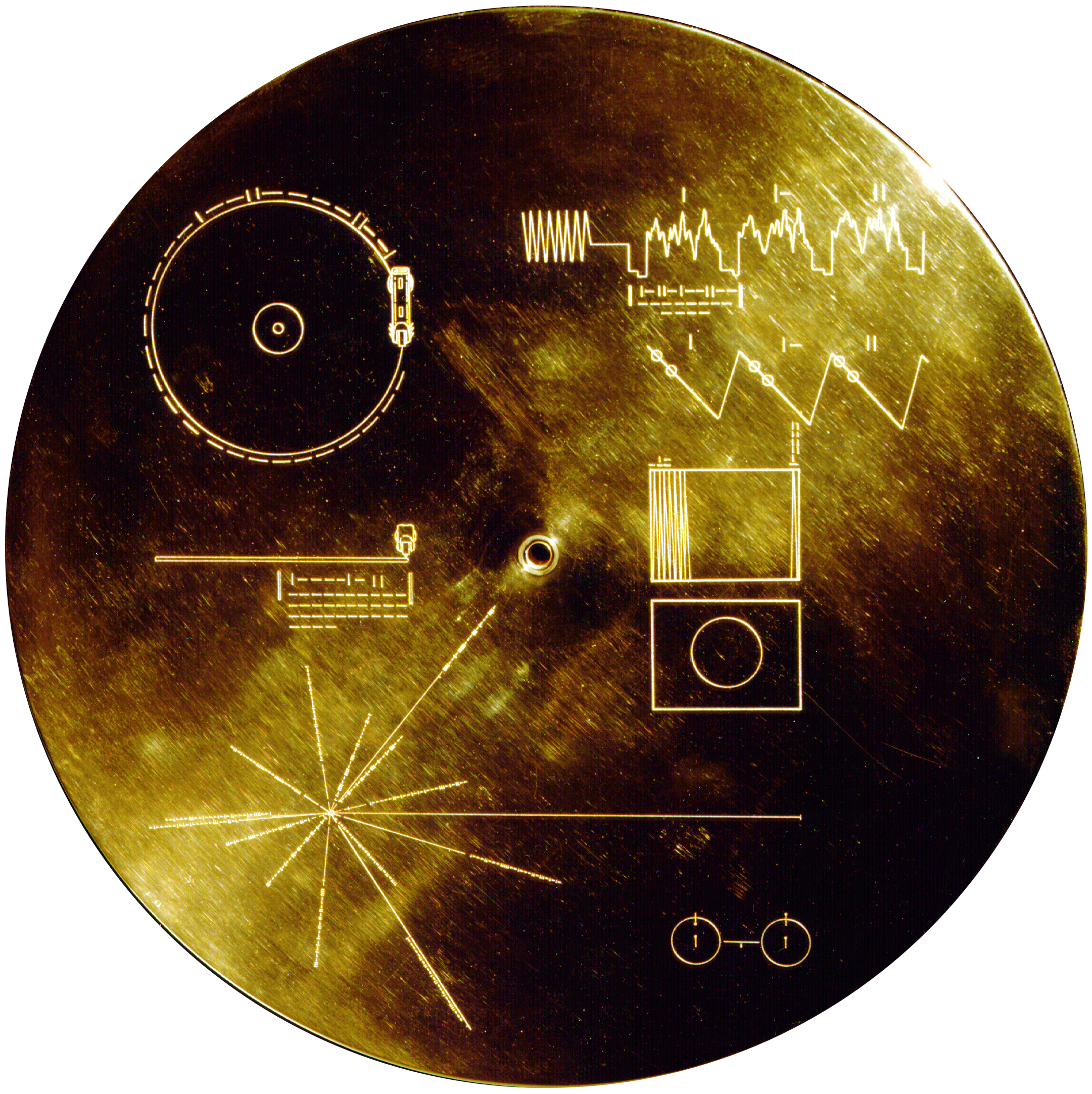

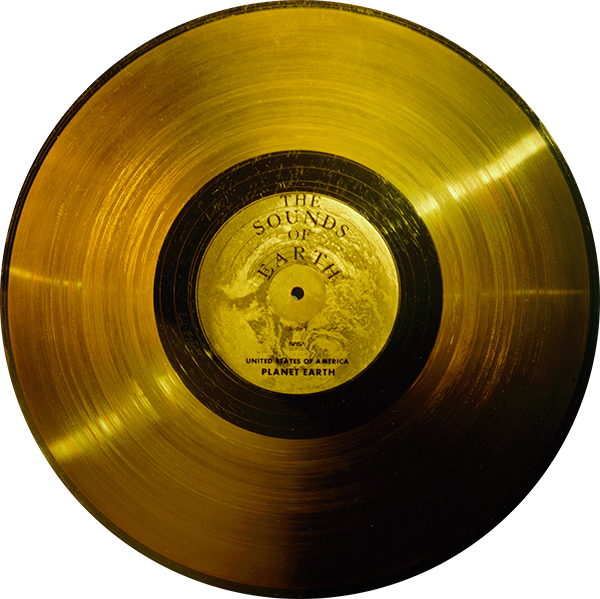

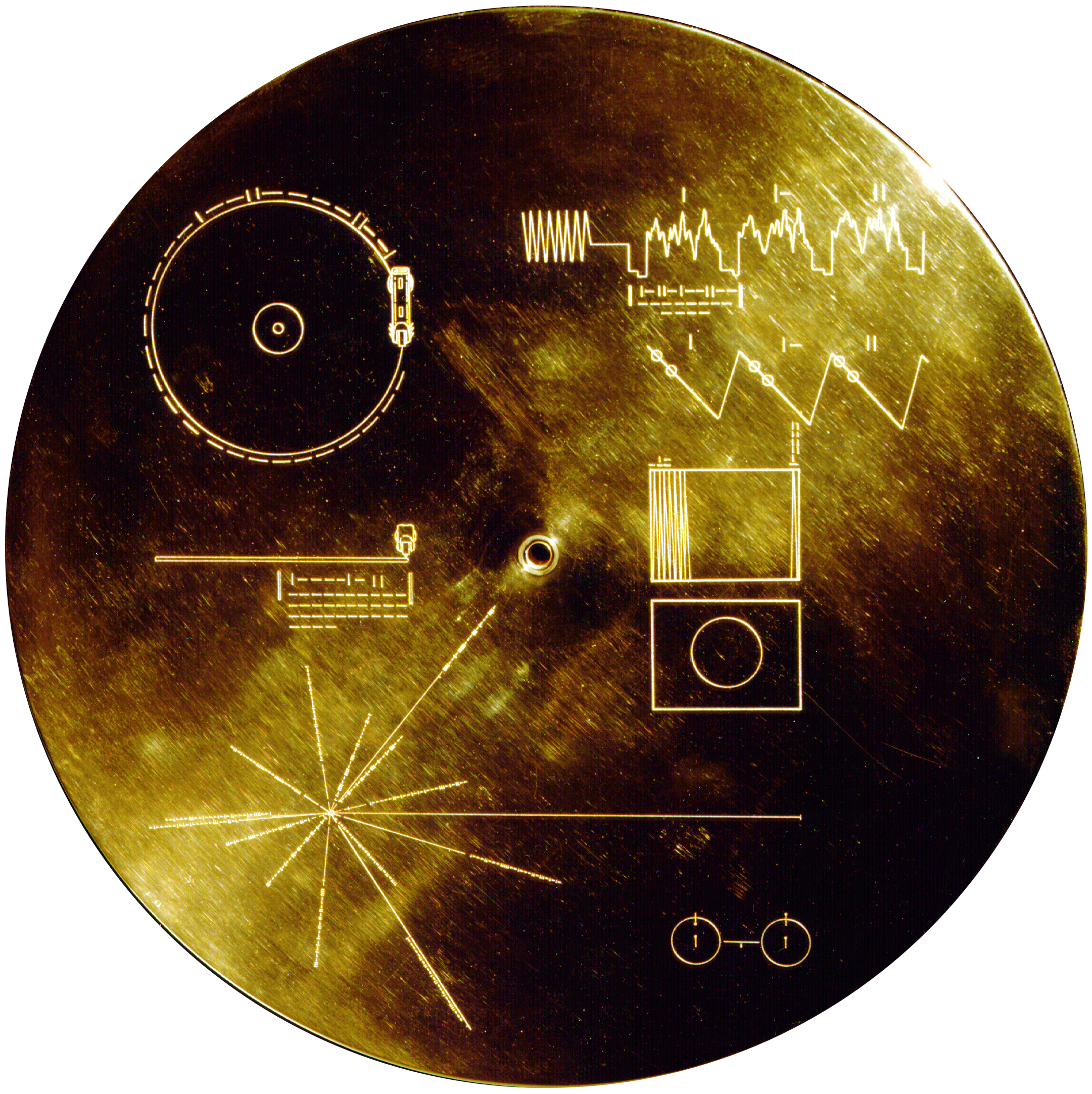

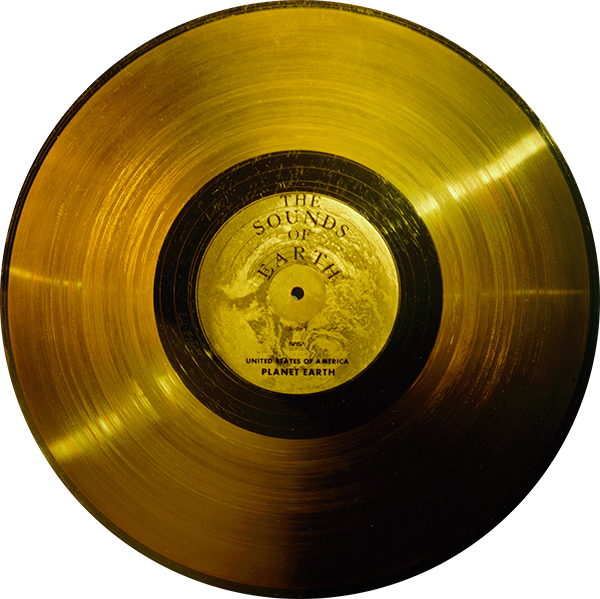

They are divided into three sections, each dedicated to a 'circle' of rhizomatic sound (of course, these circles collide and grow into each other too, and as such, all reference each other in little loops of theory): 'The Robert', in which I discuss Robert Henke (a.k.a. Monolake), Jan Jelinek, the influence of Musique Concrète, and the output of the record labels Mille Plateaux, Basic Channel, and Chain Reaction; 'The Russell', in which I discuss Arthur Russell, and the influence of the rhizomatic art-scene that occured in the '70s and early '80s in downtown New York, and 'The Holy Eno', in which I discuss Brian Eno and the ways in which he broke down the strict arboreal structures of Rock and Pop and reinvented them into the ambient and endless. Each moving disc will carry you to the next page. Enjoy the Voyage(r)!